Best viewed with

Internet Explorer.

Tourism in Japan today

Tourism delivers only app. 2% of GDP and less then 3% of jobs (OECD 2002, TIJ 2004ff). The average for OECD countries in

both respects is 5%.

Inbound tourism amounts to app. 8 mio. visitors

per year only, less than Singapore, and less than half the

global average in the ratio of arrivals/population.

Until

2014, 95% of overall revenues of the Japanese tourism

industry stemmed from domestic tourism.

The “Yokosa Japan” (Welcome to

Japan) campaign increasing the number of visitors from 5.3

mio.

in 2003 to 8.3 mio. in 2008, but in 2009 it fell back to 6.8

mio., for 2010 a maximum of 8 mio. visitors can be expected, a long way

from the aim of bringing 10 mio. visitors to

Japan by the year 2010.

2010: "Japan. Endless Discovery." is a new slogan that refers to "Japan—a

country offering inexhaustible delights". This slogan expresses our hope

that foreign visitors will come to Japan many times and gain a deep

understanding of the various tourism resources in Japan. Each visit is

an opportunity for travelers to encounter the rich nature of Japan as

represented by cherry blossoms, the history and traditional culture of

Japan, and the modern culture, cuisine and everyday life of Japan's

people.

WTM London November 2010

Only

in the last two years Japan has seen a significant

increase of tourist arrivals, almost exclusively

from China.

Conclusion:

Taking into account the four factors mentioned

before, these results are not surprising:

Domestic

tourism is an exercise in definition of

'Japanese-ness'. Domestic

tourism is an exercise in definition of

'Japanese-ness'.

Furusato tourism is not for foreigners, just the

opposite, as even trips to ’Peter Rabbit Country’ and ‘Heidiland’

become visits to “A furosato away from home”

(Rea 2000).

Furusato tourism is not for foreigners, just the

opposite, as even trips to ’Peter Rabbit Country’ and ‘Heidiland’

become visits to “A furosato away from home”

(Rea 2000).

The

guilt-ridden briefness of absense from home leads to short-term,

event-orientated travels with onsen (hot springs) as

the major non-temporary attraction. This is also reflected in the

hardware: hotels with no wardrobes, airport transit busses without

luggage departments. The

guilt-ridden briefness of absense from home leads to short-term,

event-orientated travels with onsen (hot springs) as

the major non-temporary attraction. This is also reflected in the

hardware: hotels with no wardrobes, airport transit busses without

luggage departments.

The

overarching influence of construction companies in tourism resort

development is reflected in the concentration on big projects

designed for visitors arriving in big groups and in the limited

concern on giving reasons for return-visits; a form of tourism in

decline since the end of the bubble economy. The

overarching influence of construction companies in tourism resort

development is reflected in the concentration on big projects

designed for visitors arriving in big groups and in the limited

concern on giving reasons for return-visits; a form of tourism in

decline since the end of the bubble economy.

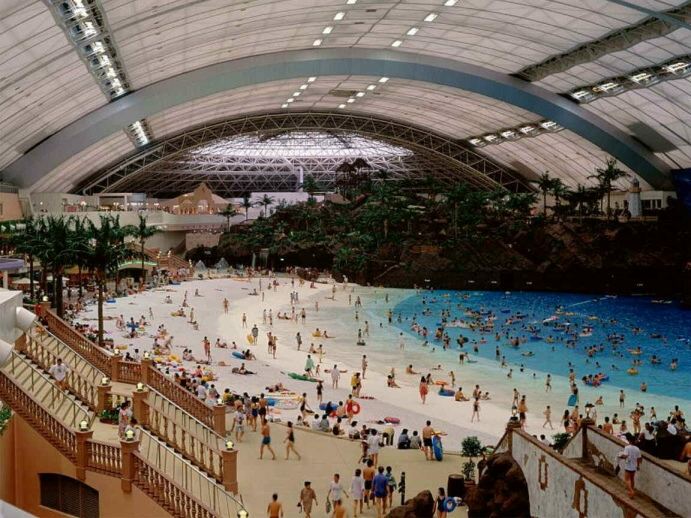

The

event-orientation expands from cultural festivals also to en-masse

visits to specific nature resources on specific occasions (blossoms,

coloured leaves, heatwave etc.). The preference of man-made nature

makes understandable the construction of huge artificial beaches

within view of the ocean like the famous biggest Ocean Dome in the world in

Miyazaki/Kyushu, only a short distance away from the real ocean. The

event-orientation expands from cultural festivals also to en-masse

visits to specific nature resources on specific occasions (blossoms,

coloured leaves, heatwave etc.). The preference of man-made nature

makes understandable the construction of huge artificial beaches

within view of the ocean like the famous biggest Ocean Dome in the world in

Miyazaki/Kyushu, only a short distance away from the real ocean.

The Acquisition and consumption of spatial and

cultural resources by tourism is comparatively limited in Japan.

The Acquisition and consumption of spatial and

cultural resources by tourism is comparatively limited in Japan.

As a positive result of its weekness, tourism in

Japan has not succeeded in forcefully opening up the inside of

sacred places like Shinto shrines to the tourist gaze. In the

cities, however, the same weekness results in demolition of profane

historic buildings, the filling-up of canals, the blocking of vistas

as part of landscaped gardens etc.

As a positive result of its weekness, tourism in

Japan has not succeeded in forcefully opening up the inside of

sacred places like Shinto shrines to the tourist gaze. In the

cities, however, the same weekness results in demolition of profane

historic buildings, the filling-up of canals, the blocking of vistas

as part of landscaped gardens etc.

Local rural cultures – idealised,

commodified – are nourished.

Local rural cultures – idealised,

commodified – are nourished.

Shirakawa-go UNESCO World Heritage Site

|